- Home

- Terry Miles

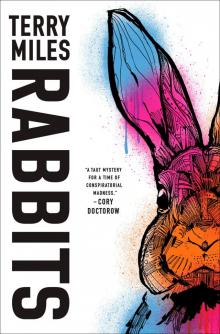

Rabbits

Rabbits Read online

Rabbits is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2021 by Terry Miles

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Del Rey, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Del Rey is a registered trademark and the Circle colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Miles, Terry, author.

Title: Rabbits : a novel / Terry Miles.

Description: New York : Del Rey, [2021]

Identifiers: LCCN 2020038865 (print) | LCCN 2020038866 (ebook) | ISBN 9781984819659 (hardcover ; acid-free paper) | ISBN 9781984819666 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Alternate reality games—Fiction. | GSAFD: Suspense fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3613.I5322426 R33 2021 (print) | LCC PS3613.I5322426 (ebook) | DDC 813/.6—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020038865

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020038866

Ebook ISBN 9781984819666

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Simon M. Sullivan, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Strick & Williams

Cover illustrations: Gareth A. Hopkins, © Terry Miles (rabbit); © Shutterstock (spray paint)

ep_prh_5.7.0_c0_r0

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1: The Scene in the Magician’s Arcade

Chapter 2: So What? It’s a Fucking Woodpecker

Chapter 3: If You Listen Carefully, You Can Totally Hear the Rhubarb

Chapter 4: The Passenger Discrepancy

Chapter 5: Baron Corduroy

Chapter 6: Sabatini vs. Graf

Chapter 7: Jeff Goldblum Does Not Belong in This World

Chapter 8: Rowing All the Boats

Chapter 9: Everything That Isn’t Rabbits

Chapter 10: Worgames

Chapter 11: Hang in There, Tiger

Chapter 12: Death and Videogames

Chapter 13: Property of Shirley Booth

Chapter 14: Second Floor Stationery

Chapter 15: We Have a Little Fucked-Up Something to Deal with Here

Chapter 16: No Playing the Game!

Chapter 17: It Smells a Little Boozy in Here

Chapter 18: Now Onward Goes

Chapter 19: Fours

Chapter 20: An Asshole in a Journey T-shirt

Chapter 21: Tenspeed and Brown Shoe

Chapter 22: The Byzantine Game Engine

Chapter 23: The Meechum Radiants

Chapter 24: You Look Like You Might Need More Than a Cookie

Chapter 25: What Else Are We Gonna Do, Play Tetris?

Chapter 26: Is That a Fucking Crossbow?

Chapter 27: The Children of the Gray God

Chapter 28: Rocket

Chapter 29: So It’s Futile and Potentially Deadly. What the Hell Else You Got Going on Right Now?

Chapter 30: Zompocalypso and the Bear

Chapter 31: Nobody Said It Was Going to Be Easy

Chapter 32: The Moonrise

Chapter 33: An Invisible City

Chapter 34: The American

Chapter 35: No Spitting on Stage

Chapter 36: East of Barn

Chapter 37: Fucking Steely Dan?

Chapter 38: R U Playing?

Chapter 39: Towel

Chapter 40: The Horns of Terzos

Chapter 41: An Unkindness

Chapter 42: Win the Game, Save the World

Chapter 43: You Can’t Hot-Wire a Fucking Prius

Chapter 44: The Night Station

Chapter 45: A Three-Hundred-Lane Fuckmonster Speedway

Dedication

Acknowledgments

About the Author

All your life you live so close to truth, it becomes a permanent blur in the corner of your eye, and when something nudges it into outline it is like being ambushed by a grotesque. A man standing in his saddle in the half-lit half-alive dawn banged on the shutters and called two names. He was just a hat and a cloak levitating in the grey plume of his own breath, but when he called we came. That much is certain—we came.

—Tom Stoppard, Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead

I first came across the game in 1983. My game theory professor took me to visit the site of the original Laundromat in Seattle. The Laundromat is no longer there, of course, but if you ask the manager of the restaurant that currently occupies the space, she might take you into the office in the back and let you see part of the original room. And, if you order a big meal and tip the waitstaff well, she might even remove the large modernist painting that hangs above the fireplace and show you the graphic of the rabbit on the wall.

Some true stories are easier to accept if you can convince yourself that at least part of them are fictional. This is one of those stories.

—SHALINI ADAMS-PRESCOTT, 2021

1

THE SCENE IN THE MAGICIAN’S ARCADE

“What do you know about the game?”

The smiles vanished from the assembled collection of conspiracy hounds and deep Web curiosity seekers, their private conversations stopped mid-sentence, their phones quickly stashed into a variety of backpacks and pockets, each of them doing their best to look cool and disaffected while unconsciously leaning forward, ears straining, eyes bright with anxious anticipation.

This was, after all, why they were here.

This was what they came for, what they always came for. This was the thing they spoke about in inelegant lengthy rambles in their first Tor Browser Web forum experience, the thing they’d first stumbled upon in a private subreddit, or a deep-Web blog run by a lunatic specializing in underground conspiracies both unusual and rare.

This was the thing that itched your skull, that gnawed at the part of your brain that desperately wanted to believe in something more. This was the thing that made you venture out in the middle of the night in the pouring rain to visit a pizza joint–slash–video arcade that probably would have been condemned decades ago had anybody cared enough to inspect it.

You came because this mysterious “something” felt different. This was that one inexplicable experience in your life: the UFO you and your cousin saw from that canoe on the lake that summer, the apparition you’d seen standing at the foot of your bed when you woke in the middle of the night on your eighth birthday. This was the electric shiver up your spine just after your older brother locked you in the basement and turned out the light. This was the wild hare up your ass, as my grandfather used to say.

“I know that it’s supposed to be some kind of recruitment test—NSA, CIA maybe,” said a young woman in her early twenties. She’d been here last week. She didn’t ask any questions during that presentation, but after, in the parking lot, she’d stopped me and asked about fractals, and if I thought they might be related to sacred geometry (I did), or the elaborate conspiracy work of John Lilly (I did not).

She didn’t ask me anything about the thing

directly.

It was always like this.

Questions about the game were most often received as whispers online, or delivered in a crowd of like-minded conspiracy nuts, in safe spaces like comic shops or the arcade. Out in the real world, talking about it made you feel exposed, like you were standing too close to something dangerous, leaning out just a bit too far on the platform while listening to the rumble of the approaching train.

The game was the train.

“Thousands of people have died while playing,” said a thin redheaded man in his early thirties. “They sweep these things under the fucking rug, like they never happened.”

“There are a number of theories,” I said, like I’d said a thousand times before, “and yes, some people do believe that there have been deaths related to the game.”

“Why do you call it ‘the game,’ and not by its proper name?” The woman who’d spoken was in a wheelchair. I’d seen her here a few times. She was dressed like a librarian from the fifties, glasses hanging around her neck on a beaded chain. Her name was Sally Berkman. She ran the most popular Dungeons & Dragons game in town. Original Advanced D&D.

“Phones and all other electronics in the box,” I said, ignoring Sally’s question. They loved it when I played it up, made everything feel more dangerous, more underground.

Everyone stepped forward and placed their phones, laptops, and whatever other electronics they had with them into a large cedar chest on the floor.

The chest was old. The Magician had brought it back from a trip he’d taken to Europe a few years ago. There was a graphic stamped onto the lid, some kind of ceremonial image of a hare being hunted. It was an intricately detailed and terrifying scene. There were a bunch of hunters and their dogs in the background bearing down on their prey in the foreground, but the thing that drew all your attention was the expression on the hare’s face. There was something dark and knowing about the way it stared out from the bottom of the image—eyes wild and wide, mouth partly open. For some reason, the hare’s expression always left me feeling more frightened for the hunters than the hunted. The chest looked like it had been manufactured sometime in the 1920s or 1930s. I always used it when I did these things; its strange patina brought an authentic old-timey-conspiracy atmosphere to the ceremony.

Once the last phone was inside, I kicked the lid shut with a dramatic bang and pulled out an ancient reel-to-reel tape recorder.

I had a digital copy of the recording, of course. In fact, I’d made the reel-to-reel recording I was about to play from an MP3. But there’s just something romantic about analog tape. Like the cedar chest, the old tape recorder was for show, and these people had come here, to this old arcade in Seattle’s University District, for a show.

They’d come from their parents’ basements, their messy studio apartments, high-rise tower penthouses, and midcentury post-and-beam homes in the woods. They’d come to hear about the game. They’d come to hear The Prescott Competition Manifesto, or PCM.

Just as I was about to press play, I heard a voice from somewhere near the back of the room. “Is it true that you know Alan Scarpio?”

“Yeah, I know Scarpio. I mean, I met him once while I was playing the ninth iteration,” I said, trying to find the person who’d asked the question in the crowd.

There weren’t that many people here, maybe forty or fifty, but the arcade was small and the bodies were three or four deep in some places.

“Most people believe Scarpio won the sixth iteration of the game,” I said.

“Yeah, we know that. Tell us something we don’t know.”

I still couldn’t find the person speaking. It was a man’s voice, but it was hard to tell exactly where it was coming from over the drone of the videogames and pinball machines.

“Alan Scarpio is a gazillionaire playboy who hangs out with Johnny Depp,” said a young man leaning against an old Donkey Kong Jr. cabinet. “He can’t be a player.”

“Maybe he played, but there’s no evidence he won the game,” said a woman in a Titanica T-shirt. “ ‘Californiac’ is the name listed in The Circle, not Alan Scarpio.”

“So then how do you explain his overnight wealth?” Sally Berkman replied—a familiar challenge when it came to Scarpio. “He has to be Californiac. It just makes sense. He was born in San Francisco.”

“Oh, well, if he was born in San Francisco, he must be the guy.” Donkey Kong Man was clearly looking to stir up some shit.

“San Francisco is in California,” Sally Berkman replied. “Californiac.”

“Wow, are you serious?” Donkey Kong Man said, shaking his head.

“How about I just play what you’ve come all this way to hear?” I said.

If I let them go on about Alan Scarpio and whether or not he was actually Californiac, the winner of the sixth iteration of the game, we’d be here all night. Again.

I nodded in the direction of a blond curly-haired woman standing near the front door, and she turned out the lights.

Her name was Chloe. She was a good friend of mine. She worked for the Magician.

The arcade was the Magician’s place.

It was an old speakeasy that had been converted into the arcade–slash–pizza joint back in the 1980s. The pizza oven had died more than a decade ago, so now it was just an arcade. Nobody understood how the Magician had been able to keep the place running through the rise of home-based and eventually handheld computer entertainment, but keep it running he did.

Walking into the arcade was like walking into another age.

The brick walls and exposed pipes in the ceiling clashed with the bright video screens and sharp 8-bit sounds of the arcade games, resulting in a strange yet perfectly comfortable blend of anachronisms.

Chloe called it eighties industrial.

The Magician was out of town on some kind of research trip, but he never came down for these things anyway.

He’d started letting a few of us use the place for meetings after the eighth iteration of the game. The Magician’s arcade became a kind of de facto clubhouse, an informal gathering place for those of us who remained obsessed with the game long after most everyone else had checked out.

I pressed play on the reel-to-reel recording, and the voice of Dr. Abigail Prescott filled the room.

…The level of secrecy surrounding the game is concerning, as are the number of candidates…STATIC…it’s chaos from the trailhead to the first marker, no algorithm can track its logic…CRACKLE…I’ve heard the underlying condition of the game described, metaphorically, as a kind of fluid, like the cytoplasm or protoplasm of a cell…STATIC…It had been dormant for a very long time when the first clue showed up in 1959. It was something in The Washington Post, a letter to the editor, and the lyrics of a song by the Everly Brothers that, when combined, provided the first indication that the game had returned. A student at Oxford put everything together and brought her professor into the thought matrix at Cambridge…CRACKLE…the name Rabbits was first used in reference to a graphic containing a rabbit on the wall of a laundromat in Seattle. Rabbits wasn’t the name of that specific iteration of the game, just like it’s not the name of this one…as far as any of us can tell, the games themselves—at least the games in this modern variation—don’t actually have names. They’re numbered by the community of players…STATIC…should be warned, we have reason to believe that the reports of both physical and mental jeopardy have been, in fact, underreported, and…STATIC.

The following was allegedly written on the wall in that laundromat in Seattle in 1959, under the hand-scrawled title MANIFESTO, and above a hand-stamped graphic of a rabbit:

You play, you never tell.

Find the doors, portals, points, and wells.

The Wardens watch and guard us well.

You play and pray you never tell.

There it was. Rabbits. The reaso

n they were here, looking for some new information, a clue, anything that might lead to evidence about the next numbered iteration: Eleven, or XI.

Had it started?

Was it about to start?

Had the tenth version really ended?

Had anybody seen The Circle?

I let the echo of Dr. Abigail Prescott’s words hang there dramatically for a moment, and then I continued with the Q&A section of my presentation.

“Any questions?”

“What can you tell us about Prescott?” A man wearing a Canadian tuxedo—dark denim shirt and light blue jeans—asked in a booming voice. He was playing a game manufactured by Williams Electronics in the 1980s, Robotron: 2084.

He was a friend of mine named Baron Corduroy: a plant I’d brought along to prompt certain aspects of my presentation.

“Yes, well, we know that Dr. Abigail Prescott allegedly worked under both Stanford’s Robert Wilson—a professor whose main area of interest is game theory as it relates to economics—and quantum physicist Ronald E. Meyers, but nobody has been able to dig up anything else of any real value on her. Some believe Abigail Prescott is a pseudonym, but nobody knows for sure.”

“A pseudonym for who?” asked Dungeon Master Sally.

“No idea,” I replied, which was true. Abigail Prescott was a cipher. It was almost impossible to find anything about her online or anywhere else—and believe me, I’ve tried.

“Where did you get that recording?” It was that voice again, coming from somewhere in the back. I still couldn’t locate the speaker.

Rabbits

Rabbits